The spectre of smoking chimney stacks has largely been banished into the history books of public health and pollution control. However urban skylines are expected to see a rapid increase in the number of new stacks as the drive for sustainable energy gathers momentum.

However, the solutions offered by some renewable fuel systems can run into problems with local planning authorities keen to prevent increase in localised levels of air pollution.

Matt Holford of WYG Environment outlines the problems and identifies the solutions.

Biomass fuelled energy systems are becoming an increasingly popular means of delivering low carbon solutions for both proposed and existing energy users, be it for domestic and community heating or large scale industrial use. There are a multitude of drivers behind the demand for biomass. Sustainable energy in new developments is a requirement within many of the evolving regional planning policies advocating low carbon energy solutions for developments. Planning authorities are also working to local targets for renewable energy, climate change emissions reductions and regional sustainability checklists. Environmental quality targets such as BREEAM and Code for Sustainable Homes carry credits for low carbon energy in construction design. Grants, such as the Bioenergy Capital Grants Scheme and the Energy Crops Programme, are available for conversions from conventional fossil fuels to biomass.

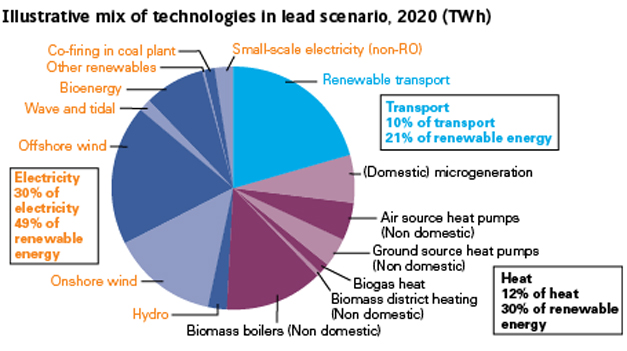

The need for low carbon energy in the form of biomass is clear. In the recently published UK Renewable Energy Strategy, 30% of electricity is projected to be generated from renewable sources by 2020, a significant proportion of which will come from biomass. Moreover as recycling rates continue to climb, so the supply of cost effective waste derived fuels will increase and the cost of this source of fuel will decrease.

Source: UK Renewable Energy Strategy 2009, (DECC).

As a strong advocate of local renewable energy systems and a former air quality regulator, Matt has a clear understanding of the tensions between biomass and protection of local air quality. WYG Environment have successfully steered a number of biomass projects through the planning process and applications for Environmental Permits.

“The downside of biomass is that the controlled combustion of the fuel – be it wood, energy crops or process by-products, generates emissions of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and respirable particulates (PM10). Waste derived fuel also has the potential for emissions of a range of other airborne pollutants including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals.”

Communities across the UK are currently exposed to exceedences of National Air Quality Objectives for both NO2 and PM10 concentrations. All such communities have to be declared as Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) by the local authority. Currently over 230 local authorities have one or more AQMAs and many more locations are very close to the Objectives. Therefore many air quality regulators, whilst recognising the huge environmental value of biomass, have significant concerns that even relatively small scale biomass facilities will contribute to existing Air Quality Objective exceedences or tip the balance, taking existing areas that meet the Objectives over the edge.”

Environmental Protection UK and Local Authorities Coordinators of Regulatory Services (LACORs) have recognised the challenge and have issued guidance to local authorities on biomass and air quality as well as developing downloadable tools for screening the potential impacts of associated emissions. These are proving useful and popular in order to enable both biomass providers and the regulators to determine whether biomass facilities in areas of good air quality are likely to cause concern.

However, the tools are not yet sufficiently robust to enable cumulative assessment of the effects of emissions in combination with other sources or for use in areas of existing poor air quality. For example, if a proposed facility is to be installed next to an existing busy road, the combined emissions from both traffic and the biomass facility need to be fully assessed.

Matt suggests that demonstrating to planners that biomass is not a threat to local air quality need not be cumbersome, time consuming or expensive. “A really robust assessment can be generated by atmospheric dispersion modelling. Using a fully validated dispersion model, such as ADMS or AERMOD, the effects of local meteorology, terrain, surface roughness, buildings, atmospheric chemistry and other uncertainties can be used to provide confident predictions of emission impacts at exposure locations. This is particularly important where the effects of the biomass emissions are being assessed in combination with road traffic and where ideally a separately verified air quality dispersion model will have been produced to assess exposure to the local road traffic emissions. Research over recent years has established that air quality dispersion models frequently underestimate road traffic emissions of NO2. It is important therefore that dispersion modelling results of traffic emissions have verification adjustments based on a comparison of local Councils’ own air quality survey data with predicted concentrations. The effects of the biomass emissions can then be included within the traffic dispersion model to determine the cumulative effect of both sources. Using Councils’ own air quality monitoring data also gives them much more confidence in the accuracy of the model predictions”.

There are certain practical difficulties when taking forward planning applications involving biomass, but Matt believes that these should not delay the process.

”It can be the case that the inclusion of biomass facilities comes relatively late in the evolution of development proposals and may be included specifically at the request of the local planning authority. The exact specification of the biomass system is often not fully defined at the planning application stage. Therefore, whilst the developer may have reached the point of specifying the thermal capacity of the proposed plant, it is frequently the case that the proposed fuel and exact appliance model has not been determined. Biomass fuels differ significantly in their emissions per unit mass and therefore an air quality assessment may by necessity be based on worst case or typical fuel type emissions. Worst case scenario assessments are perfectly adequate for air quality assessment purposes as they provide consideration of the maximum potential impacts associated with a development.”

The size of the energy unit and fuel type will determine what, if any, further statutory consents are required. Very small units require no consent (other than planning where necessary), however medium and larger units greater than 0.4MWth may require either a chimney height consent under the Clean Air Act 1993 or an Environmental Permit under the Environmental Permitting Regulations 2007. The EPUK / LACORs guidance usefully summarises the regulatory management of different types of plant.

Matt believes that the absence of complete information about the proposed biomass facility should not give cause to planning authorities to unnecessarily delay or refuse an application.

“It is incredibly frustrating from a developer’s perspective to bring forward proposals promoting a ‘green’ energy scheme aimed at protecting global air quality only to find that permissions are delayed due to conflicts with local air quality objectives. Most potential planning issues with biomass facilities can be addressed by the use of salient conditions or informatives which protect local air quality. Potential conditions could for example require detailed air quality modelling to determine the stack height and discharge velocity or specify an appropriate abatement method, fuel type, fuel quality, maintenance arrangements, maximum thermal capacity or emission limits. All of these can be determined after planning consent has been granted and subject to a suitable appraisal of the local constraints on emissions.”

The potential contribution of biomass towards the huge challenges of low carbon energy provision is clear. It is a proven technology ready to deliver relatively low cost, dependable energy, and as such has been placed at the forefront of the Renewable Energy Strategy. Environmental Regulators, through the planning and regulation process, are well placed to support the delivery of biomass solutions and should be encouraged to do so, whilst playing a key role in managing and mitigating associated environmental effects.